Read this story in Nepali: देश कृषिप्रधान, तरकारीदेखि खाद्यान्नसम्म आयातकै भर

Since the start of the monsoon season (in mid-July), the price of staple rice has increased by up to NPR 300 per sack. Narendra Adhikari, a grocery store owner in Lokanthali, Bhaktapur, mentions that the price of popular rice varieties like Jeera Masino and Sona Mansuli, which are commonly cooked in Nepali households, has gone up. According to him, there are many rice ‘brands’, and the price varies according to the brand.

"A month ago, a sack of rice that was being sold for Rs 2,200 to Rs 2,300 is now priced at Rs 2,600," he says. "The Sona Mansuli rice, which was being sold for Rs 1,700 to Rs 1,800, has now reached Rs 2,000."

"A month ago, a sack of rice that was being sold for Rs 2,200 to Rs 2,300 is now priced at Rs 2,600," he says. "The Sona Mansuli rice, which was being sold for Rs 1,700 to Rs 1,800, has now reached Rs 2,000."

In the first week of July, neighboring India decided to ban the export of all rice varieties except Basmati. This decision immediately led to a price hike in Nepal. According to a monitoring report by the Department of Commerce, Supplies and Consumer Protection, the price of a 20–25 kg sack of rice has increased by up to Rs 300. In just a week, the price per kilogram rose by as much as Rs 14.

"There is enough rice stock in the market to last two-and-a-half to three months. However, right after India announced the export ban, prices were increased overnight," says an under-secretary at the Department of Commerce, Supplies and Consumer Protection, on condition of anonymity. "We have a shortage of manpower for regular and strict monitoring. The government's failure to monitor is the reason behind the price surge. The primary cause is the massive legal and illegal import of rice from India."

Rice is only one of the essential commodities whose price has gone up high.

Prices of salt, lentils, cooking oil, beaten rice and sugar have also gone up. Traders have been increasing prices under various pretexts and the Indian rice export ban has been used as an excuse. The price increase in other daily essentials is often cited as an effect of budget speech.

According to the officials at the Department of Commerce, the price of food staples has increased by 4% to 13% since mid-July. This price rise, which started from July, has made the upcoming Dashain and Tihar festivals more expensive for households.

Bitter story of sugar

In recent weeks, the price of sugar has increased by at least Rs 10 per kilogram. While sugar was available for Rs 100 per kilogram three weeks ago, retail traders are now selling it for a minimum of Rs 110. As the festive season approaches, prices are expected to increase even further, according to a seller from ‘Big Mart’ in Baluwatar, Kathmandu.

The shortage of sugar is not just a problem this year; it happens every year. Consumers always end up paying high prices for sugar, making the story of sweet sugar quite bitter. Last year, during the festive season, to prevent sugar shortages, the Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies had assigned the Food Management and Trading Company Limited and the Salt Trading Corporation to import 10,000 tons each. These government institutions have a 50% customs duty exemption when importing sugar. However, both companies claimed the import was too expensive and chose not to import sugar. The same situation is being repeated this year.

Following this, the government turned to the private sector for sugar imports. On June 12, 2024, the Ministry of Industry, Commerce, and Supplies sent a letter to the Department of Industry instructing them to begin the process for the private sector. On June 16, a notice was published, inviting contractors to apply for the import of 19,000 tons of sugar. While nine private companies applied, they eventually decided not to import sugar, citing the lack of customs duty exemptions.

Nepal has more than a dozen established sugar mills but they face their own challenges. Each year, the country has to rely on imports from India and Brazil for sugar. As a result, consumers can never get sugar easily when they need it. There is even a history of people queuing at Salt Trading Corporation for an entire day just to get a kilogram of sugar.

Profit: Middlemen have it all

On June 18, 2023, in Kalimati, Kathmandu—where the country’s largest vegetable and fruit depots lie—the traders threw 30,000 kilograms of tomatoes onto the streets, protesting that they were forced to sell them for as little as Rs 2 per kilogram. They claimed that the market price did not cover production and labor costs, which led to their frustration.

The Kalimati Fruits and Vegetable Market Development Board confirmed that around 30,000 kilograms of tomatoes were dumped on the streets that morning. While traders were discarding the tomatoes, ordinary people were purchasing them for Rs 45 per kilogram on the same day.

Farmers often sell tomatoes for Rs 250 per crate at the beginning of the season. However, during the peak season, they have to sell them for just Rs 50 per crate (Rs 2 per kilogram). By the time these tomatoes reach consumers, they have to pay as much as Rs 60 per kilogram.

This year, the shortage of onions has already hit, and prices for tomatoes, cabbage, mushrooms and other vegetables have risen significantly. It’s unclear how long consumers will continue to bear the burden of these rising prices.

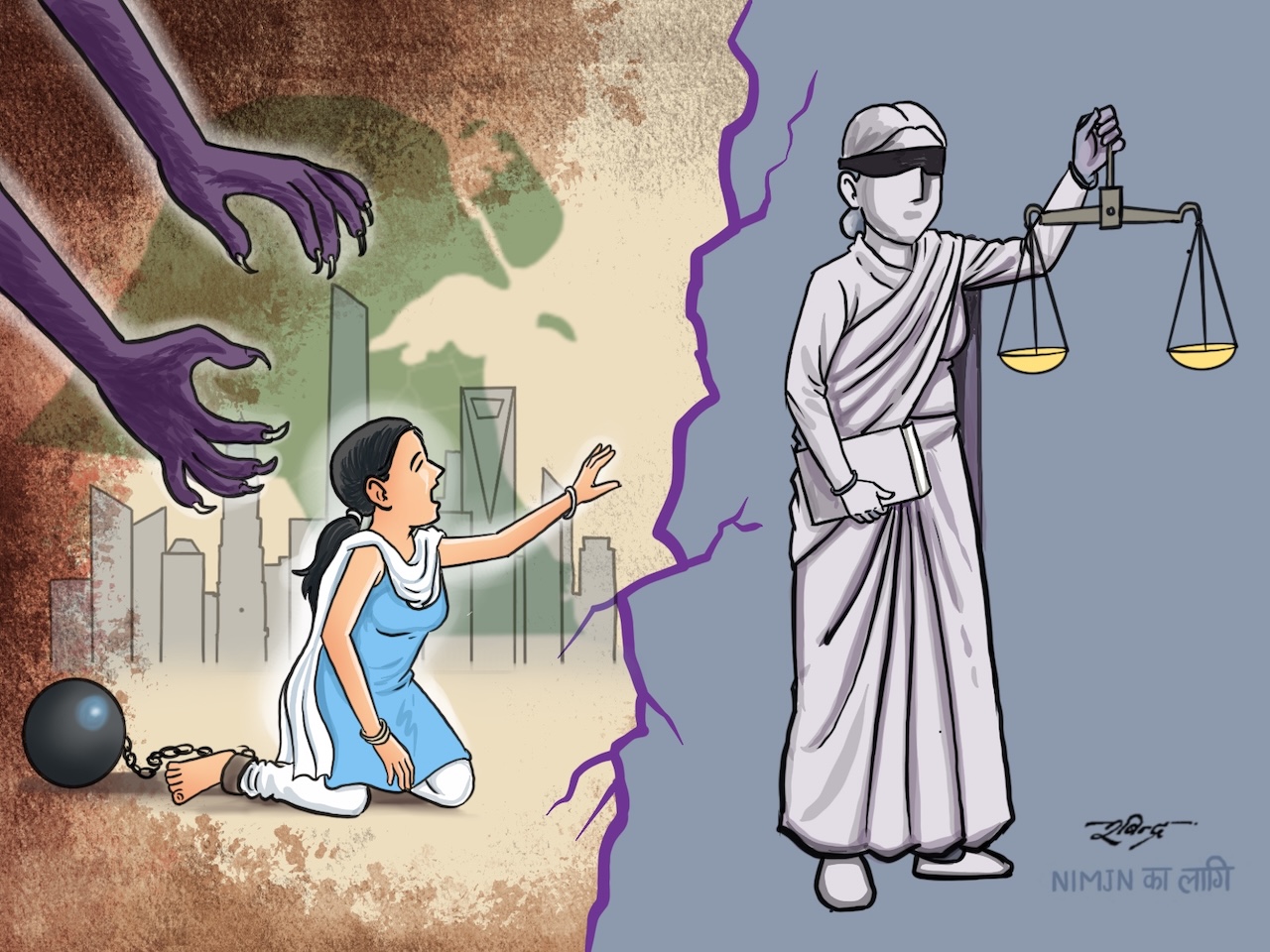

Nepal has a widespread problem with ‘syndicates and middlemen’ across various sectors, and vegetables are particularly affected. According to Jyoti Baniya, President of the Consumer Welfare Protection Forum and an advocate, both farmers and consumers are being exploited due to the dominance of middlemen, the intermediaries. Experts say that every day vegetables must pass through at least seven middlemen before reaching consumers.

These middlemen include (1) local collectors, (2) collection centers, (3) transporters, (4) large wholesale sellers, (5) small wholesale sellers, (6) transporters to retail shops, and (7) retail shops, before finally reaching the consumers.

Each of these middlemen adds a profit margin of Rs 2 to Rs 10–15, leaving the hard-working farmers and consumers to bear the costs. Middlemen often take a commission of 20% to 30% while doing little work. Due to a lack of effective government monitoring and intervention, middlemen have become increasingly unscrupulous, says Prem Lal Maharjan, President of the National Consumer Forum. He remarks, "The government never introduces plans to relieve consumers. The price hikes often occur with the government's complicity. The level of exploitation faced by consumers might be unique to Nepal."

In addition to dependency on imports and skyrocketing prices, a more alarming issue is the influx of tons of vegetables from India, which displaces Nepali produce. For instance, pumpkins, which are grown in abundance in Nepal, often remain unsold, forcing farmers to feed them to livestock or let them rot in the fields. At the same time, pumpkins are being imported from India in large quantities.

According to Chandra Kishore Thakur, Information Officer at the Plant Quarantine Office in Kakarbhitta, during the fiscal year 2023/24, Nepal imported 10,574 metric tons of pumpkins worth Rs 211.48 million.

According to Thakur, in fiscal year 2023/24, Nepal imported 51,113 metric tons of tomatoes worth Rs 1.02 billion and 14,787 metric tons of green chilies worth Rs 295.74 million from India. Additionally, during the same period, 28,869 metric tons of bitter gourds valued at Rs 577.38 million, 15,029 metric tons of okra worth Rs 300.78 million, and 7,836 metric tons of beans worth Rs 156.72 million were imported, according to Thakur.

In the same year, from the eastern border alone, Nepal imported 3,835 metric tons of sponge gourd worth Rs 677 million, 1,575 metric tons of squash valued at Rs 315 million, 12,828 metric tons of pointed gourd (parwal) worth Rs 256.56 million, 692 metric tons of onions worth Rs 130.84 million, 5,585 metric tons of carrots valued at Rs 111.7 million, and 1,902 metric tons of yam worth Rs 38.04 million from India. Farmers complain that their locally produced vegetables are not being sold as vegetables and grains imported from India enter Nepal without proper quarantine checks.

Unpaid, cash-strapped: Plight of dairy farmers

You've probably never bought milk on credit from a shop. After all, dairy companies don't sell milk on credit. They take cash with one hand and hand you the milk with the other. However, these dairies are purchasing milk from farmers on credit and not paying them.

Nepal's government-owned Dairy Development Corporation (DDC) has also not made timely payments to farmers. DDC owes more than Rs 2 billion to farmers. In response, farmers and private dairy industries staged protests in December last year, where they spilled thousands of liters of milk on the streets. On December 12, 2023, the government agreed to release the outstanding payments to farmers and dairy industries.

An agreement was signed to release the pending payments in installments. However, even by early March of 2024, the farmers still hadn’t been paid, leading them to protest again. On March 2, 2024, another agreement was made between the government and farmers. According to this new agreement, farmers and dairies were supposed to receive all payments due by April 3, 2024. But even this agreement was not implemented, forcing the farmers to continue their protests. From June 7 to June 18, 2024 farmers sold milk by wearing black armbands in protest. On June 19, 2024 , farmers went to picket DDC’s central office in Lainchaur, where 48 farmers were arrested by the police.

The protests did not subside with the arrests. On June 30, 2024, the government made another agreement with the farmers. According to this agreement, all payments due up to April, 2023 were to be cleared by July 11, 2024.

However, the farmers still have not received the promised payments.

There are 1,872 milk-producing cooperatives under the Cooperative Union. Milk is collected from over 46 districts, including Kavre, Sindhupalchok, Makawanpur, Chitwan, Morang, Sunsari, Jhapa, Ilam, Panchthar, Rupandehi, Kapilvastu and Baglung. The DDC collects milk from farmers through eight different projects. Together with private dairies, the DDC collects 1.2 million liters of milk daily from 600,000 families. Despite this, the farmers have not been paid for months or even years. Meanwhile, milk continues to be imported into Nepal from countries like India, the UK, Australia, South Korea, Denmark, Japan, Germany, Kuwait, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and Qatar.

Import of millet

According to the Department of Central Customs Office at Tripureshwor, during the first six months of fiscal year 2023/24, millet worth Rs 437.065 million was imported. During this period, 8,906.51 metric tons of millet were imported. Interestingly, by the end of the fiscal year, the import value of millet had reached Rs 854.256 million. According to Chandra Kishor Thakur, Information Officer at the Plant Quarantine Office in Kakarbhitta, 17,797 metric tons of millet, valued at Rs 854.256 million, were imported from India and other countries in FY 2023/24.

Thakur further mentioned that in FY 2022/23, millet worth Rs 513.12 million, amounting to 14,035 metric tons, was imported from India. This indicates an increase of Rs 340.9 million in millet imports during FY 2023/24compared to FY 2022/23. As millet production in Nepal declines, imports from India and other third countries are on the rise, according to Thakur.

During the same period in FY 2023/24, buckwheat worth Rs 14.491 million (197.12 metric tons), barley worth Rs 11.902 million (301.17 metric tons), and Junelo (a type of grain) worth Rs 19,000 (340 kilograms) were also imported, according to the Department of Customs.

Millet can be grown at altitudes ranging from 60 meters to 3,650 meters, making it suitable for both lowlands and hillside regions. The government has declared rice, wheat, maize and millet as national crops. However, this declaration appears to be limited to formalities. There is an old saying in Nepal, "Sita khane bhitta laage, kodo khane jodaha" (meaning millet is considered food for the lower classes). Millet is a crop that requires minimal irrigation, relies mostly on rainwater, and doesn't need much fertilizer. In recent years, millet has become a favorite dish even for the affluent, with dishes like ‘millet momo’ and ‘millet dhindo’ becoming regular items on the menus of fancy hotels and restaurants. However, due to government neglect, millet production has not been given the priority it deserves.

Budget on agriculture: Tall talk, low delivery

Whether it is policy programs or the budget itself, the government has not stopped using flowery language to promise incentives for farmers, even if only on paper. In the budget presented on May 28, 2024 by Finance Minister Barshaman Pun, agriculture was listed as the top priority among the five transformational sectors. To transform the agriculture sector, he presented numerous attractive programs although the government he was minister of collapsed before these could be implemented.

Pun said: "Agricultural commercialization and modernization will be promoted to increase production and productivity. Investments in agriculture will be increased through government, private, cooperative and development partner contributions, and the decade from 2081 to 2091 (BS) has been declared the decade of agricultural investment."

He further stated in Clause 32: "To ensure fair prices and markets for agricultural products, contract farming involving the government, farmers and businesses will be promoted. Firms involved in the collection, processing and export of agricultural products will provide farmers with necessary inputs such as fertilizers and seeds. In return, these firms will purchase the agricultural products and, based on the quantity produced, the government will provide subsidies for fertilizer, seeds, agricultural extension services, and interest on loans." Finance Minister Pun allocated Rs 57.29 billion for the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development.

However, apart from the day the policy program or budget is announced, there seems to be no one genuinely advocating for farmers.

According to former Agriculture and Livestock Minister Ghanashyam Bhusal, a significant portion of the agriculture budget is spent on ‘saris and vehicles’. He claims, "Less than half of the budget allocated for agriculture is utilized. In reality, there is no one truly advocating for agriculture and farmers in Nepal."

As a result, the import graph continues to rise, while exports are dwindling. The trade deficit reached Rs 1.4406 trillion in just one year. The 2021 national census revealed that 62% of households in Nepal are engaged in farming. Despite such a large number of farmers, the country is increasingly dependent on imports for vegetables and grains.

Former Minister and Member of Parliament Jwala Kumari Sah, who led the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development three times for brief periods, admits that the reliance on imports is due to the lack of focus on self-sufficiency in production. She says, "The primary task of the agriculture sector is to become self-sufficient in production and reduce imports. To achieve this, agriculture must be the top priority. The government and all political parties must focus on agriculture, regardless of political philosophy."

'Self-reliance in agriculture' only on paper

‘Fundamental problem of Nepal’s agriculture is that the state and government lack a long-term policy for self-reliance.’

Dr. Krishna Prasad Poudel, Agricultural Expert

The state and the government have not provided the necessary support to farmers where they need it most. Agriculture is a culture intricately tied to nature. Nature is not in our control, and farming is similarly dependent on it. After sowing seeds, will they sprout? Will the crops grow, and will they yield grains? All of this depends on nature.

Although, in recent times, humans have been able to bring nature and agriculture somewhat under control, it is still not fully in our grasp. In the past, people used to take all the risks in agriculture themselves. After the government introduced policies to provide assistance, agricultural insurance and other support systems began to emerge. However, the state has not provided as much support as it should have. Just as our economic and political system is flawed, the state's treatment of agriculture is equally flawed. In this sense, the state has deceived agriculture and farmers significantly.

The growing dependency on food imports and soaring prices can be attributed to three main factors, which the state has failed to address properly.

Farmers are abandoning agriculture. They are doing so because the expenses they incur in farming do not match their income. High-quality fertilizers and seeds are not available on time. The production cost is high compared to the investment. As a result, farmers are leaving farming.

Agriculture has fallen into the hands of traders. Traders are solely focused on making profits, without concern for health and quality. Few exceptions aside, most of Nepal's agricultural activities are profit-driven. Farmers, with their limited resources, cannot do much on their own. Everything is now in the hands of traders, and the state has not been able to regulate their harmful practices. Agriculture is no longer aligned with nature. Natural agriculture incurs minimal costs, but once it becomes disconnected from nature, the costs rise, and we become dependent on external sources. This is why imports are increasing, and prices are skyrocketing.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war have also affected farmers and agriculture. Ukraine is one of the world's largest reserves of oil and grain. Ten days after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, I wrote that the prices of grain and oil would increase, and that the Nepali government should strengthen its self-reliance. Others knowledgeable about agriculture had also made similar statements. Sure enough, on the 21st day, the price of mustard oil skyrocketed.

All countries are now focused on ensuring their food security. Even India has imposed export bans to focus on its own food security and increase production. If India imposes a full import ban, 25% of Nepal’s population will face hunger, leading to chaos.

The slogan of 'self-reliance in agriculture' remains limited to paper. The fundamental problem of Nepal’s agriculture is that the state and government lack a long-term policy for self-reliance. The government’s agricultural policy is unclear and impractical. Subsidies in agriculture are being misused, given to unproductive sectors. When the government itself is corrupt and lacks clarity, it is natural for imports to rise and prices to escalate.

The social psychology changed by the ruling class and middlemen is another reason for our dependency on imports and tolerance of price hikes. In the past three to four years, a mentality has been imposed that nothing can be achieved by staying or working in Nepal. The sight of people, young and old, standing in lines with passports discourages those trying to work in agriculture. The agricultural produce they create doesn’t get fair market value and they are treated with neglect. Essentially, our farmers and agriculture are being crushed day by day. It is the state's responsibility to instill confidence in farmers, but with the state abandoning them, farmers have become helpless.

No matter how much we talk about patriotism or nationalism, there is no nationalism for someone who cannot fill their stomach. Forget about nationalism – if someone cannot eat or provide for their family, they won’t even consider their parents as their own. A country that relies on food imports and cannot sustain its own population with domestic agricultural production cannot be self-reliant or nationalistic. The statistics on food imports show that we are becoming increasingly dependent, which is a great tragedy for our country.

[Based on a conversation with Dr. Poudel]

Read Our Republishing Policy here.